Review: Modern Poetry by Diane Seuss

Modern Poetry opens not with reverance but a question: "What can poetry be now?"

Book: Modern Poetry

Author: Diane Seuss (Wikipedia)

Publication Date: March 5, 2024

Publisher: Greywolf

Overview: The role and meaning of poetry in contemporary life, working-class experience, formal experimentation, the legacy of the Romantic and Modern poetic canons.

Where To Buy: Book Outlet

Review

Diane Seuss’s Modern Poetry opens not with reverence but with a question: “What can poetry be now?” This collection does not merely answer this question but it thoroughly interrogates the assumptions of the poem’s purpose, and in that very motion, gives us something urgent and alive.

Seuss arrives at her inquiry from particular terrain: a working-class upbringing, a Midwestern landscape, a history of “outsider” status. What she brings to the page is both voice and vantage. In the poem “My Education,” we read:

“You can’t hide / from what you made / inside what you made.”

This line is emblematic with the poet tracing her craft back to self-making, to error, to revision.

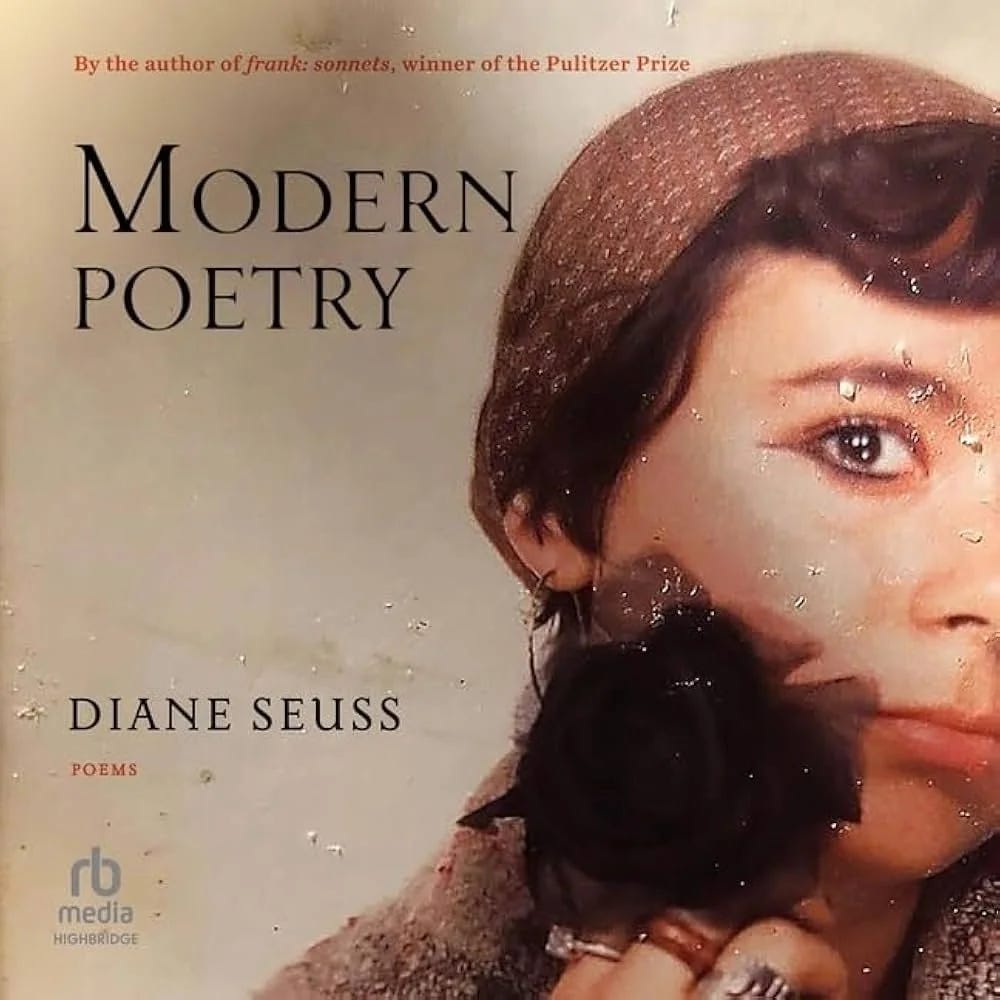

The book is arranged like a syllabus, like a textbook, its title tongue-in-cheek, or perhaps very serious: Modern Poetry. The cover is a Polaroid of Seuss at eighteen, perched between youthful rebellion and poetic reckoning. Through the sections that follow we meet “Ballad,” “Fugue,” “Rhapsody,” “Ballad That Ends With Bitch”, musical forms repurposed, retooled, made to hold what she needs them to: grief, memory, the site of the everyday.

Seuss’s craft is fierce.

She writes about unpaid bills, raccoons, goats, and neon signs and then asks us to read them as elegy, as witnessing. In Poetry Foundation’s review this is described as a post-Romantic lyric autobiography, “in reinventing the 19th- and 20th-century poetic canons, deconstructs how poems and poets are made, and what poems mean.” The tension between the “Romantic” (Keats-ish aspiration, lyric expansion) and the “Modern” (fragmentation, outsider voice, self-aware craft) pulses through every page.

Consider the poem “Little Fugue with Jean Seberg and Tupperware,” where Seuss maps cultural consumption, outsider longing, the mess of what we are taught to admire. Or “Ballad in Sestets,” where the poet admits “I would like to have better ideas / than the ideas I have” — and then reproduces the leap anyway, in metaphor, in image, in the collision of lofty and low.

What this book leaves us with is not tidy resolution, but a rehearsal of the larger question: Can poetry still matter? For Seuss, the answer is yes — but only if poetry is willing to belong to its makers, to its machines, to its dirty room, to its draft and bleed. “Modern poetry is waste,” she writes in interview, acknowledging that what is discarded may still matter.

From the perspective of a press like Ink & Ribbon — committed to craft, permanence, and the printed word — Modern Poetry stands as one of the more vivid proofs that poetry can do more than reflect: it can revise. It can hold the dialectic of care and noise; it can exist in the bookstore and the rough landscape. It can be sharp, funny, bruised, and still ask us to stay.

If Modern Poetry is a volume for anyone who believes that poems are not just artifacts but acts, then perhaps it is also a template: how to press the old forms into new urgencies; how to remain legacy-aware without being trapped by it. Seuss shows us that the poem is not finished when it leaves the page; it continues in the reader’s breath, in the margin, in the glare of forgetting.

In the slow press of Ink & Ribbon’s mission — to reject disposability, to affirm the objectness of the book, the presence of the poem — this collection feels essential. It reminds us that the printed page can still carry friction, resistance, revelation. That the poem need not be comfortable to be necessary.

The Inkwell is published by Ink & Ribbon Press — a nonprofit poetry publisher dedicated to craft, discovery, and the permanence of the printed word.

Byline: G. K. Allum is the founder of Ink & Ribbon Press, a nonprofit poetry publisher dedicated to craft, discovery, and the permanence of the printed word. A poet, photographer, and growth strategist, he brings two decades of creative and marketing experience to his work in the literary arts. He lives on Bainbridge Island with his wife, children and bengal cat.